Only within the last few years, speaking generally, has there arisen a physician, here and there, who has recognized the necessity for studying and treating the individual patient instead of his nosological clan or disease. They have called upon their fellows to bestir themselves out of their crude and primitive methods; to search out from among the wilderness of symptoms which becloud almost every case of serious illness the characteristics that represent the man himself and his condition, and to base their treatment upon these.

On this phase of the subject Dr. George Draper in his brilliant article, “Science, Art And The Patient,” in Harpers for last March, said:.

“In just the same degree by which the quality of one mans laugh in health differs from that of another, does his manner of sneezing or feeling pain in sickness differ, or his method of resisting or failing to resist bacteria, or of dealing digestively with a Welsh rarebit after midnight”.

Noting that the greater part of medical research during the past twenty-five years has been and is still directed upon the external agencies of disease, Dr. Draper pointedly asks if the immense amount of capital and effort thus expended has yielded results which justify the almost complete lack of support for study of the other essential disease-producing factor the unique re-activity of a given individual. Emphatically, it may be said that it has not; but there are very few medical men who seem to know it, or who, knowing it, make the least effort to mend their ways.

During my long professional life I have known and been in more or less intimate relations with several painters. Some of them have been and still are my friends. Justice and Mr. Thomas Craven compel me to say that I have not found them to be “inferior beings” nor devoid of minds. They are really quite human, Mr. Thomas Craven to the contrary notwithstanding. Not one of them presented the stigmata of degeneration he describes.

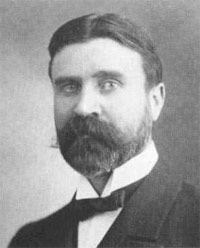

While sitting recently for my portrait by a painter of well- deserved and more than local renown, I took the opportunity to make a mental portrait of him. For this purpose I observed him closely, seeking to analyze not only his personality but his method of studying and portraying his sitter, being sure that I should thus be able to determine whether he had a “mind” or not. In doing this I had the advantage of a preliminary analytical study from the standpoint of a physician; for he had previously been under my professional care.

As it is my custom to make a psychological as well as a physical examination of my patients, I was prepared to observe him more accurately in the exercise of his art. My background, to use an artists phrase, was already laid in and the outlines and masses of the figure sketched. We were already pretty well acquainted with each other and on very friendly terms.

I liked my painter from the beginning of our acquaintance. There was something so modest, so ingenious, so friendly, so considerate about him that one could not help liking him. Although a man of forty, he was so like a bashful boy in some respects that I did not for some time give him credit for possessing certain more mature mental qualities and powers which I perceived later; although I might have inferred them if I had stopped to recall his successes in overcoming the peculiar difficulties incidental to making contact, engaging interest, arranging sittings and painting soul-satisfying portraits of several great leaders in the professional and business world Henry Ford among them.

Such men know, or have excellent means for learning, the true value of things they want or which are offered to them. They know men, they know minds and they are “canny”. It is not easy to get them away from their offices and the guards who surround them, engage their interest and hold their attention in such a way as to lead them to reveal their real selves; for that is the para- mount purpose of the portrait painter.

A true portrait is not a mere reproduction of a flitting expression of the countenance, nor the fixed form that the features take in repose which, by the way, is all the camera is capable of recording. It is, as it were, a composite made up of many expressions, all quickly noted as they pass, registered by the artist, partly with his brush and partly in his memory while he works, until all are blended and unified into individuality.

It is a portrayal of the man himself in all his essential characteristics; not a mere mask nor a transient expression showing only one phase of the subjects character and personality. And such portraits are being painted today not many, to be sure, but some enough to give Mr. Thomas Craven the “Retort Courteous,” if not to proceed through the other Shakespearian degrees to the “Lie with Circumstances” and the “Lie Direct”.

In order to be able to paint such a portrait the artist must not only know his sitter, but he must be able on occasion to work at lightning speed. He must have the mental perception and perfected technique gained only by long and arduous study and practice. This technique is psychological as well as physical.

It includes the mental ability to engage and hold the interest and attention of the sitter in ways which will bring animation into his attitude and facial expression. The sitter must not, while work is going on, be permitted to relax into a listless attitude with a tired or bored air or with a face devoid of expression. When he becomes tried he needs and must be given a rest, but while posing it is part of the painters art to keep him alert and interested in something.

Here is where the painters skill and experience, his intuition, his tact, his knowledge of human nature, his social qualities, as well as his technical ability, will all be called into play if he has them for this is his art. If he has not learned beforehand what subjects interest his sitter and how to introduce them, the painter must do so during the sitting. Unless he can talk entertaining himself, or get the sitter to talk, he will fail.

He will, therefore, try to get his subject to describe or explain something, to narrate his experiences, or involve him into telling his favorite stories. Not for his use is the photographers traditional phrase, “Now look pleasant, please”; for the average sitter is not like the movie actor who is supposed to be able to “register” artificially at command, the entire gamut of emotions. His registration must be spontaneous and real, not assumed. The ability to evoke this in his sitter is one of the most important factors in the artists equipment. Does Mr. Craven think he could do this if he had no mind?.

Are there any such painters? Well, there is my friend Bennett Linder for one. He certainly got me interested. He not only talked, but he made me talk and did it so skillfully that I did not realize what he was up to till afterwards. When I accused him of spoofing me he laughingly denied it and averred that he was really interested in what I had been saying.

The canvas showed such a remarkable development during that period, however, that I could only account for it by crediting him with the ability to do at least six different things at once; ask me intelligent questions, listen, keep up the thread of the conversation, observe my facial expressions, select and mix his colors and apply them effectively at lightning speed. It was a feat of mental perception, concentration, co-ordination and manual dexterity that I have rarely seen equalled and never surpassed. Hence, I feel quite certain that he is one artist who has a mind and knows how to use it. Doubtless there are others similarly gifted, but doubtless Mr. Thomas Craven will not seek them out, nor admit that they exist. So be it.

The amount of “mind” that goes into a painted portrait may be judged by the kind of reaction excited in the minds of those who view it assuming, of course, that they too have minds and are sincere in their expressions. Confronting a product of a real portrait painters art one who views it attentively will get an impression of “livingness” that is almost startling. The expression seems to change almost momentarily while one is looking. A young friend and patient of mine who had just seen the portrait of myself in the artists studio was so impressed by it that he called me on the telephone to tell me about it.

“At first while I was looking at it,” he said, “I saw you as you usually are in your office serious, concentrated but sympathetic. I turned away a minute to speak to Polly (his wife) and when I looked again I was astounded and delighted to see a peculiar twinkle in your eyes, a faintly smiling, half quizzical expression that I have often noticed when I have been with you. You seemed about to make some droll remark to me Polly said, I can just hear him say Belladonna!”.

Illusions, of course, but not altogether so, for as a matter of fact all, or several, of these characteristic expressions are actually painted on, or into, the canvas during the process of “modelling”; but it is so skillfully done by a master that they do not appear at first sight as separate expressions. They seem to spring to the surface while one is looking intently at the picture, and vary with the mood of the observer. Technically, they are the concrete result of a blending of forms and planes similar to the blending of colors. They give the portrait its character and individuality and stamp it as a work of art.